A few months ago I wrote about an example of

Defense Housing in Rogers Park built for war workers in 1942. These were the result of strict Federal guidelines permitting only defense-oriented projects to receive priority use of building materials. With the end of the war in sight by 1944 the country began to prepare to absorb about 16 million returning veterans. These soldiers had left in the middle of a decade-long housing shortage, and would be returning to all parts of the country, not just areas that had benefited from wartime construction.

Below is a draft of an article intended for the upcoming issue of AREA Chicago. It will probably change a bit once I get comments from the editors.

In September of 1946 the Chicago Tribune printed an article announcing plans for a 92 unit development intended for WWII veterans on 3.6 acres on Ridge Avenue, north of Devon. At the time this was a sparsely developed area, dotted with the single family frame houses and small truck farms which comprised much of the early character of West Ridge.

The architect was listed as Edwin H. Mittelbusher of Howard T. Fischer & Associates, Inc. Mittelbusher served as the Assistant Chief Architect for the Chicago office of the Federal Housing Administration from 1940 to 1945. Howard Fisher was the founder of General Housing, Inc. and pioneered the development of pre-fabricated housing. He served as the director of the development board of industrial housing for the National Housing Agency in 1946-1947. In short, this development was designed by people skilled at working within a bureaucracy.

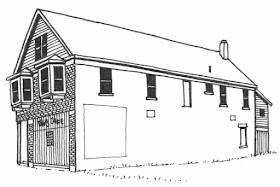

|

| Damen-Ridge Garden Apartments, 1946. Perspective view from Ridge looking Northwest. |

The project itself consists of eight two-story brick veneer buildings with hipped roofs arranged around green inner courts. The outer courts accommodate parking areas. The buildings are a restrained version of the Colonial Revival, with modern touches, such as concrete sun shades on the first floor corners and entrance stairs illuminated with large glass block windows. They were constructed as a combination of 4 and 5 room rentals. This project was initiated under the Veteran's Emergency Housing Program (VEHP), but between the time these buildings were planned and when they were completed the VEHP became functionally obsolete.

The Veterans Emergency Housing Program was developed and proposed by Wilson Wyatt, former mayor of Louisville, Kentucky, at the direction of President Truman. The initial goal was to create 2.7 million housing units within two years to serve veterans, many of whom returned to crowded conditions and shared housing situations. To accomplish this wartime price and wage controls were intended to be maintained and priority was given to housing development through a series of initiatives. The bill establishing the VEHP was signed into law in May of 1946.

Six months later Republicans took control of Congress and eliminated much of the economic controls, resulting in a sharp increase in costs in response to pent-up demands. The program had been responsible for over 1 million housing starts in 1946, but many stood half-constructed due to shortages of building materials. Soon a home that would have sold for $6000 in 1945 was priced at $8,000. This was at a time when many veterans were marrying and beginning a family. Rather than buy a home at an inflated price many chose to find rental housing. This is the era reflected by the buildings in West Ridge constructed specifically for the returning veterans.

|

| 2212-30 W. Farwell and 2213-31 W. Morse, 1946. |

The construction of these brick buildings was advertised in the Chicago Tribune in November of 1946. The architects and builders are listed as Charles and Arthur Schreiber, who established their firm in 1938 and later went on to design many modernist structures in the Southwest. These 4 and 5 room rentals were intended to accommodate 74 veteran families. They are similar to earlier courtyard buildings in the neighborhood, but with large sunken courts and parking along the alley. The restrained details, portal windows, and limestone door surrounds suggest the Moderne style, which lent itself to construction on a budget.

|

| 6102-6122 N. Hamilton, 1947. |

In February of 1947 the Chicago Tribune published an article about these three buildings, which were constructed as cooperative housing for veterans and designed by architect Clarence Johnson. They're traditional in form and ornamentation, including decorative entrances, corner quoins, water tables and limestone details. These are located on wide lots but are quite shallow due to the cemetery immediately west. The cooperative ownership structure is unusual, and the article claims that this is one of Chicago's first cooperative apartment developments. Titles to these buildings were conveyed to a corporation, and each veteran buyer purchased shares of that corporation. Cooperative ownership was (and is) rare in Chicago, and has been largely eclipsed by condominium ownership. Of the three developments examined here, this is the only one which wasn't intended as a straight rental property.

While I don't intend this to be a comprehensive look at veteran's housing in Chicago (or even in West Ridge), it does provide some examples of the types of development which were feasible immediately following WWII. And in some ways it sets the stage for the suburban explosion of the 1950s, when affordable single family homes became widely available, changing the character of the American landscape.

Sources

1. The AIA Historical Directory of American Architects, 1956. Accessed online at

http://communities.aia.org/sites/hdoaa/wiki/Wiki%20Pages/1956%20American%20Architects%20Directory.aspx

2. Chicago and Evanston Vet Apartment Units Approved. Chicago Daily Tribune; Sept. 8. 1946. Accessed through ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Chicago Tribune (1849-1988). Pg. NA

3. Work Started on Three New Flat Buildings. Chicago Daily Tribune; Nov.10, 1946. Accessed through ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Chicago Tribune (1849-1988). Pg. 43

4. Finish Homes in Early Vets’ Co-op Project. Chicago Daily Tribune; Feb. 23. 1947. Accessed through ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Chicago Tribune (1849-1988). Pg. WA.

5. To Hear Only Thunder Again: America’s World War II Veterans Come Home. Mark D. Ellis. Lexington Books, 2001. Accessed through Google eBooks.

6. The Veterans Emergency Housing Program. William Remington. Law and Contemporary Problems, Vo. 12, No. 1, Housing (Winter, 1947), pp. 143-173. Accessed through JSTOR.