Few buildings convey the historic character of the city as recognizably as the Chicago cottage. They

can be found throughout Chicago in working and middle-class neighborhoods. Many were built in the 19th and early 20th century, but in reality the cottage never went out of style, it just transformed itself again and again.

|

| 2322 N. Cleveland, 1895 |

In general terms a cottage is one or one and one-half stories in height and built of wood or brick. After the great fire of 1871 the city rushed to rebuild itself- in wood. It took a few more years (and another fire in 1874) to impose strict regulations requiring fireproof construction within city boundaries.

|

| 2044 W. Iowa, c. 1880 |

Most cottages are rectangular in plan, and fit on a typical Chicago lot (25' x 125'). They have front facing gable roofs and offset front entrances. Architectural styles were often expressed through the window and door surrounds, as well as the cornice. Most have a basement, although many early cottages just have a crawlspace.

|

| 1334 S. Karlov, 1890s |

Cottage were constructed by individuals, but were often part of larger real estate developments. Early Chicago had block after block of cottages, often taking advantage of mass produced ornamentation and informed by popular pattern books of the time. Most common are those in the Italianate style, which decorative hood moldings and paired brackets under the eaves. The one above is an example of the Queen Anne style, which used elaborate surface treatments and varied textures.

|

| 3703 W. Wrightwood, c.1890 |

Here's another Queen Anne cottage with a tripartite window configuration on the second floor with a sunburst pattern. The porch is covered with fish-scale shingles.

|

| 2020 W. Augusta, 1899 |

Above is an unusual example of a greystone cottage with a projecting bay. "Greystone" is an Indiana limestone commonly used for multi-family homes in Chicago in the 1900s and 1910s.

|

| 1530 N. Greenview, 1910. |

This cottage uses a simplified gothic vocabulary, with paired arched windows and elaboration of the gable parapet.

|

2042 W. Iowa, c.1900

|

I'm not sure exactly what happened, here, but I suspect this cottage was rebuilt with stepped parapet. Work this extensive usually resulted from a major damage, such as a fire. But behind it you can still see the classic massing of the cottage.

|

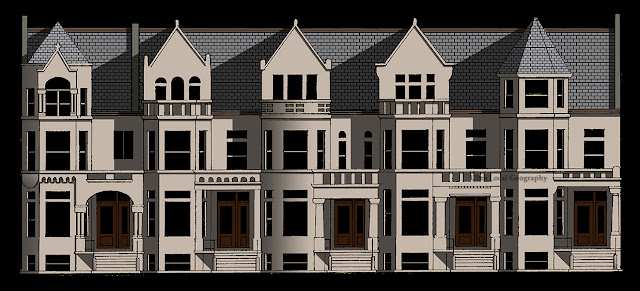

2404 N. Bernard, 1906

|

This is an amazing classical revival treatment of a cottage. It uses a gambrel and triangular roof, and incorporates all sorts of pressed metal details, including a lantern motif to ornament the spring-points of the roof. There's an unusual palladian window configuration on the second floor, with stepped limestone lintels.

|

2731 W. Haddon, 1894

|

And just to illustrate the breadth of the classical revival style, here's another one with elaborate ornamentation. The centerpiece the segmental arched window with a sunburst motif. I can't even adequately describe the cornice...

|

6413 N. Troy, 1958

|

The post WWII building boom of the 1950s built many neighborhoods in Chicago. These used a new palette of materials and construction methods, many of which were developed during the war and quickly adapted to private development. But its hard to improve on the overall massing and utility of the cottage.

|

6401 S. Austin, 1964

|

The 1960s brought an even greater variety of materials and ornamental approaches. This is considered a raised ranch, but for me it's a Chicago cottage pointed into the future.