|

| Early Courtyard Building Pattington Apartments, Chicago 660-700 W. Irving Park Rd. Published in the Inland Architect, 1903 |

So recently I've been looking at courtyard apartment buildings. They're surprisingly easy to overlook. After all, it's the things we see every day that are the easiest to ignore. But when I say I've been looking at them what I really mean is I've been making detailed lists, taking photos, and digging through old copies of The Architectural Record.

Specifically, I'm looking at buildings in Rogers Park built between 1910 and 1929. This covers their earliest appearance in the neighborhood through the building boom of the 1920s. And I've limited myself to walk-ups no higher than 3-stories. Or 3 1/2 if you count the raised basement. Even with these limitations there are still over 200 buildings in the neighborhood which would meet these conditions.

Thanks to Google, Bing, and the City of Chicago online zoning map it's been relatively simple to put together a list. I've been augmenting it with information from the County Assessor's website. And I've started to collect building footprints using Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps (available online through the Chicago Public Library). Although I'm sure this will evolve as I uncover more information, I've put together some graphics to help define and categorize these buildings.

Courtyard apartments are mainly a collection of L-shaped modules. The simplest is a single module oriented to create a side court open to the street. Two linked modules create a U-court, which seems to be the most common type. Three modules can create an S-court, which is a narrow court open to the street in combination with a hidden interior court. And four L-modules can create a multi-court building.

[I apologize for the candy coloring, but it seemed like a good idea at the time.]

As I define them, a courtyard building must create at least a partial sense of enclosure while providing some green space which remains visible from the street. These four types cover the majority of these buildings, but the variety among each individual type is surprising, and will require separate posts.

The axonometric views above give some sense of the massing created from the different module combinations. It also suggests how the different configurations could be chosen to fit on various sizes of city lots. But the graphics themselves start to raise additional questions. How many standard city lots are needed to accommodate the different types of courtyard buildings, and how much of the lot can the building cover? Can formulas be derived for each of the types which predict the size and configuration of the buildings? How much green space is there per unit? All questions I can't yet answer, although I have high hopes for my evolving Excel table.

Above are building footprints taken from Sanborn Fire Insurance maps. I've used a variety of colors to better illustrate the configuration of the individual units. Small rectangles indicate stairs-- yellow for exterior or open stairs and color-coded for interior. By code, each unit needs two egresses and natural light and ventilation for all living spaces. These units represent an evolution from the typical narrow Chicago apartment to a wider, more rectangular configuration with increased cross-ventilation.

Courtyard apartments are partly characterized by the number of entrances on the buildings. While earlier apartments commonly made use of interior corridors, courtyard apartments will generally have one entrance and stair for every six units (two units per floor). The space that would have been used for corridors is then incorporated into the units. As a side-note, stairs which served a limited number of units helped give the impression of a smaller, more intimate building. But in some ways even the largest of these buildings function collections of six-flats.

|

| Click for slightly larger version |

The height of these buildings is also significant. If they were any taller than 3 stories they would have been required to be fire-proof, which would have bitten into the profits of the developer. And at 3 stories there was no need to install elevators, another good measure to cut costs. And of course, any taller than 3 stories and people are genereally less willing to climb the stairs.

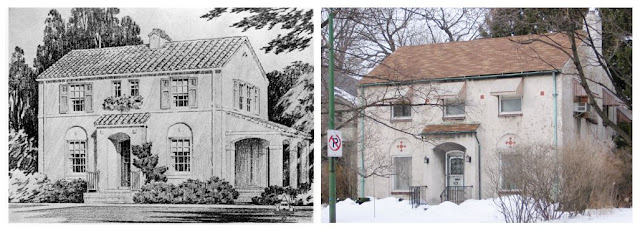

These courtyard types first appeared as luxury housing. They could be seen as scaled-down versions of the French-style flats on East Lake Shore Drive. As such they were widely published in architectural literature (see the plan for the Pattington Apartments above). Some early critics saw these as a distinctly Chicago form, although examples can be found widely. In the 1920s a simplified version, with less frills but better suited to middle-class incomes, spread throughout the city. They embody many systems of architectural ornament, most often Classical Revival, Tudor Revival, and Italian Renaissance Revival. These same styles were common for other buildings of the era, both commerical and residential.

So I don't want to get bogged down in this initial post, but I'll be taking a closer look at each of the four variations as well as identifying some of the less typical types of courtyard buildings. And maybe a brief jog into financing, social history, and the Chicago Zoning Code of 1923...

And finally, here's a link to a blog posting from A Chicago Sojourn, which I think is a good photographic introduction to the variety of the form.

6414 N. Paulina, 6960 N. Ashland, 7001 N. Wolcott, 1414 W. Lunt